AUTHOR, STUNT MAN, AND ALL-ROUND ADVENTURER, TEEL JAMES GLENN BREAKS DOWN THE WRITING OF GREAT FIGHT SCENES ...

I have spent the better part of the last 37 years being beaten, stabbed, set on fire and hit by cars – for money.

That’s right, I’ve been a stunt monkey since I got out of art school and ran into a guy at a party who was looking for someone to storyboard a film. The film had a fight scene, I designed it, got cast in the film, did the fight and never looked back.

I studied martial arts, boxing, gymnastics and then the more exotic skills like car hits, stair falls, fire burns and most enjoyably, sword fighting (I got to do that with Errol Flynn’s last stunt double).

But time marches on and, as they say, there are old stunt men and bold stuntmen but no old, bold stuntmen. I eventually returned to my first love, writing, and launched on a career of pulp adventure tales. It seemed only natural that my stories reflected my background and had a lot of action (my literary idols were Burroughs, Howard and Hammett). Soon I got a reputation for my actions scenes.

I applied the same principles to the action in my stories as I had to all the fights I choreographed over the years but I now also, as the writer, was responsible for determining when and where action scenes showed up in the story and this fact made me do some serious examination of how and why I wrote them.

Here are a few thoughts that might help my fellow writers...

Since the first storyteller sat around a campfire spinning tales of gods and heroes it has been a given that a little action makes a mildly interesting story into a real grabber. Put your hero or heroine in physical jeopardy and you can have a winner. Conflict is the key and physical conflict, i.e., a fight, is often the answer.

It is not the only answer, to be sure, and emotional conflict is the essence of real drama, but the line where drama ends and adventure or melodrama begins is an iffy one. If the level of your drama is high, if the characters are convincing and we as a reader care about what happens to them then you can get a frenzy of worry out of us by having a villain try to club our hero. Or shoot him or…you get the idea.

A writer has to be careful that the action is not hastily added in or used as a patch between talking head scenes. This cheats the reader and the writer of great opportunity to explore how the characters react in stressful situations and the chance to inform the readers of some facts about the characters. Where did the character learn to do a certain move, or what about the fighting style of the bad guy triggers a memory from our heroine’s past?

Since the fight has to serve the purpose of the story you have to use the same criteria as any journalistic or dramatic story. Ask yourself, ‘is this fight necessary?’ If it is then you can use the old six questions: Why, Who, How, Where, What and When?

WHY

Why is this fight the solution to this moment of the story, instead of a dialogue scene? After all, Shakespeare put the fight at the end of Hamlet for two very strong reasons. It was the dramatic climax that brought together several plot threads, and it was used as a device to reveal the true personalities of the major participants: Laertes regrets using the poison, Hamlet is proud of his swordsmanship, Claudius reveals his cowardice etc.

There are four chief reasons to have a fight in a story, though often a fight (or action scene) can and should serve more than one of these reasons.

To amaze or confuse a character.

To scare a character.

To conceal/reveal some plot point within the smoke and mirrors of an action scene.

To reveal or accentuate a character trait.

WHO

Who is involved in the action; the principal? A secondary character? If so, what is their stake in the confrontation (their personal why)?

HOW

How did the fight come about? How does it end? And in what state are the participants when it is all over? Will there be lingering effects? And will the effects be physical or mental or both? There is also the mechanical how of a fight; that is, how to plan it out. You can’t build a house without a plan and just as you would plan out a book or story by making an outline you must do the same thing with the ‘story’ of a fight.

WHERE

Where does the action take place? Is it an interesting enough place, i.e. a kitchen, a garage, a spaceship port? What makes that place of particular interest? Does it add color to the story, or is it just a drab background, a diorama in front of which the action takes place?

WHAT

What is involved, physically in the fight? A sword fight; if so, what style? Or styles. Do they use the objects at hand or did they bring the ‘death dealers’ with them. (Jackie Chan movies are especially good at finding clever things to do with found objects in action scenes—you don’t have to be ‘clever’ funny but you should clever smart).

WHEN

When is it appropriate to have a fight instead of a non-physical solution? I know I keep stressing this, but that cuts to the heart of the situation of many literature snobs who will not deal with any ‘action’ because they feel it cheapens the purpose of a story.

FLAVORS OF VIOLENCE AND THE ‘OUCH’ FACTOR

A grim, down and dirty knife fight might be fine for a thriller, but wrong for a romantic comedy. Once you understand that it hurts you can think about the ouch factor, that is, how much damage and how much recovery time.

This is where the flavors come in – how you balance these elements: how real, how much pain, and to what end the action in the scene in the story determine if the fight is farce or frightening.

So how does it break down – what makes a fight funny or scary or realistic?

EXERCISES TO LIVEN YOUR FIGHT SCENES

Not everyone is a fight choreographer, but every one can choreograph a fight. Really. The first thing you do is to decide the type of fight. For argument’s sake we will assume you want to design a sword fight with short swords.

Now, I know you probably don’t have any short swords sitting around the house. No problem. Get some rolled up newspaper and a congenial friend/mate/sibling. Now, slowly, as in really slow like an old Six Million Dollar Man episode, walk through five or six moves.

Just like a slow motion dance. Then write it down; but in the writing, the newspapers become real swords and you are moving at breathtaking speed.

Now this may not be possible. You might not be able to physically execute the moves, or have a long suffering conspirator to collaborate with.No problem. Just let the inner child out and get a couple of movable action figures. Even the art store pose-able figures with no features. Tape some short swords made out of pop sticks into their hands and let them do your fighting for you.

Then write it all down.

When painting students are learning their art they are instructed to copy the paintings of great master, stroke for stroke and it is considered perfectly okay. No legal hassles at all. Okay, now that you’ve read the stories, or story, you have a big task ahead: rewrite it. That’s right, take Conan or Tarzan or whomever and the general situation of the scene and –without peeking – write your version of it. May be your only chance to write your hero without a copyright lawyer running after you. It’s best to do it for a scene you read ‘last book’, or earlier in the book, and once you decide on the scene don’t go back and peek. Cheaters never prosper!

Then put it aside for a day or so before going back to compare them. It doesn’t matter if you unconsciously copied some phrases or exact actions, it is bound to happen, it is the idea that you can achieve some of the energy or flow of the story – and who knows, you might improve on it. Could happen!

What is the appropriate level of you character’s skill?

The choices extend beyond purpose and tone for a fight, it must also be appropriate to the time, place and character.

I mean, really, Babe Ruth should not be swinging an aluminum baseball bat unless it’s a time travel story and if your 1860s cowboy hero starts throwing jumping martial kicks he better be named James West!

A certain amount of credibility with your reader is purchased from their imaginations with the preconceptions of what they expect verses what is credible or possible.

Martial arts have points of origin: you can’t have a Bowie knife fight before 1827 because the indomitable Jim Bowie hadn’t invented it (or perfected his brother’s invention – whichever version you believe). And fighting with a Bowie is significantly different than than fighting with other knives, or swords, because while it shares characteristics of both it is its own beast.

Thus you see how very important to the believability of the story it is to get the How or with what you characters fight with. Those factors and their attitude to the action are all great means to understand who they are and how they fit into the mosaic of the story’s world.

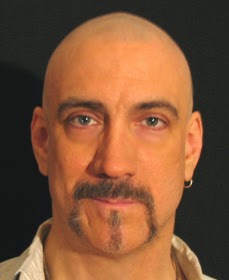

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Teel James Glenn has written on theater, stunts and swashbuckling related subject matter for national magazines like: Aces, Black Belt, Echoes, and Fantastic Worlds of E.R.B. and fiction for MAD, Weird Tales, Peculiar Stories, Pro Se Presents, Fantasy Tales, Afterburns, Another Realm, Blazing Adventures!, Tales of Old and other magazines. He has 30 books in print including his newest The First Synn: The Bloodstone Confidential from Pro Se. He received the Pulp Ark Award for best author in 2012.

He has taught staged/stunt combat at colleges and choreographed fake violence for over 300 plays and 55 Renaissance Festivals. He has been a martial artist most of his life and stunt coordinator for 70 films He has appeared as an actor and stunt performer in over three dozen more as well as all the New York soap operas. He has also conducted seminars for theatrical groups from Florida to Canada in staged combat and taught self defense and anti-rape classes nationwide. You can keep up on his adventures at www.theurbanswashbuckler.com

No comments:

Post a Comment